JUDSON Bennett’s Coastal Network

OPINION

Dear Friends,

I write about lots of things concerning politics and about Delaware in general. It looks as if former Delaware U.S. Senator and former Vice President Joe Biden is actually going to be the President of the United States. Indeed, it is my profound belief that he does not deserve to be President, that he is the most corrupt politician in U.S. history, and his election was the result of grotesque voter fraud.

Regardless, Delaware apparently is going to have one of its own in charge of our future, which to me is extremely frightening. What this man represents and the people he is surrounding himself with, will put the United States on a path to complete Socialism, a life without hope, and the existence of mediocrity. Indeed, my sincere desire is that the election be invalidated by the Supreme Court and sent to Congress to decide. I wanted to get that point across before going further.

Regardless, my disdain for Biden and the devastation I am certain he will bring, along with my chagrin that he is so corrupt, is not the point of this article. Actually folks, Delaware almost had another character be a viable candidate for President. He was not blatantly corrupt like Joe Biden, but his probable racism and Southern sympathy, were the “RUBS” that disqualified him from getting there.

I find this Delaware history personally interesting, because I had a relationship of sorts with many of the direct relatives of Thomas F. Bayard, Sr. My parents had a house on Lewes Beach, 5 houses away from the Bayard family. I knew the father Tom Bayard and his wife Josephine Linder (Tom was the grandson of Thomas Sr. and great grand-daughter Josephine (Dosie) Bayard was my first girlfriend. After the death of my wife, I had a 3-year relationship again with Josephine (Dosie) Bayard in Palm Beach, which did not end well. Interestingly, I attended St. Andrew’s School with great-grandson Tim Bayard (Thomas F. Bayard III), who was Josephine’s brother. Indeed I know the whole family, brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, and uncles, great-great grand-children. I know everything about them all — good and bad. Once the Bayards hooked up with the DuPonts, their influence, power and wealth grew stronger. They all have very substantial trust funds. Remarkably, some even have tattoos, which would probably make a few of the dead relatives roll over in their graves. What I also find fascinating is that the Bayards are descended from Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutchman who had been the 17th-century general director of the colony of New Netherland, which at one time, included the Dutch settlement which is now Lewes, Delaware). Interestingly, I have learned recently that I am a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant as well, which probably has a few Bayards rolling over in their graves also-LOL.

All this being said, Thomas F. Bayard, Sr was a remarkable man who actually kept Delaware from being a Confederate state. He was the first ambassador from the U.S. to the United Kingdom. Unfortunately, his actions, vocal sympathies, and suspected racism, kept him from achieving these ambitions. Please read the article below which clearly tells you who Thomas F. Bayard, Sr. was, how he affected Delaware, and the fact he came close to being President. So Be it!

As always your comments are welcome and appreciated.

Check out the interesting article below.

Yours truly,

JUDSON Bennett-Coastal Network

https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2020/10/30/before-biden-man-delawarean-who-came-closest-presidency/6052282002/

Before Biden, this man was Delawarean–

who came closest to presidency.

Delaware News Journal

Joe Biden has already been a heartbeat from the presidency after serving eight years as Barack Obama’s vice president.

Now he’s poised to possibly become the first U.S. president to call Delaware home.

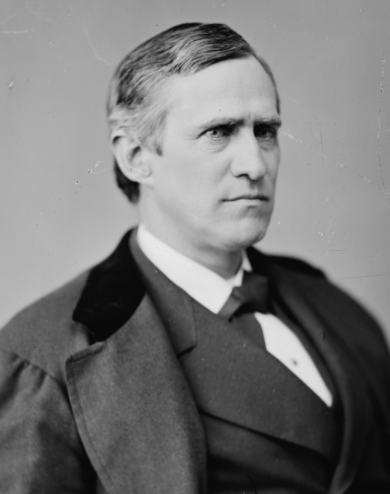

But before Biden’s arrival on the national political scene nearly 50 years ago, Thomas F. Bayard Sr. held the distinction of the Delawarean who came closest to landing in our nation’s highest political office.

Even though he didn’t, Bayard was well known nationally and internationally as a statesman.

While serving as a U.S. senator from 1869-85 and then secretary of state, during periods when there was no vice president, Bayard was next in line to become president.

He also unsuccessfully bid to become the Democratic Party’s nominee to run for president in 1876, 1880 and 1884. His compassion for the struggling Southern secessionists during and after the Civil War may have come back to haunt him.

“This ardent championship of a stricken section made him suspect in the North and helped to blight his Presidential prospects,” Georgetown University professor Charles Callan Tansill wrote in “The Congressional Career of Thomas Francis Bayard, 1869-1885.”

“His sympathy for the South was regarded by the Radicals as something akin to treason, and they helped to create the impression that his nomination as President would be a breach of faith with the millions who had worked and fought to save the Union. In the South many politicians were fearful of making Bayard their standard-bearer because large groups of voters in the North resented his affection for Dixie.’’

As it was, Bayard had actually played a key role in preventing Delaware, a border state, from also joining the Confederacy during an 1861 speech in Dover.

“Delaware was pretty close to seceding,” said great-grandson Richard Bayard, a 71-year-old Wilmington attorney and public policy operative. “That speech was credited with helping Delaware not secede, to stay in the Union. He suffered damage from it but he kept Delaware in the right place and that was good.”

Some of Bayard’s greatest distinction came during his final political assignment serving as the first U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom during president Grover Cleveland’s second term from 1893-97. He eased often-tense relations between the countries and set the tone for their alliance.

Cleveland was among the pallbearers when Bayard was laid to rest at Old Swedes Church in Wilmington two days after his death, at age 69, on Sept. 28, 1898.

“Although born in Delaware,” Judge Charles Swain of Florida eulogized that day, The Morning News reported, “he long since belonged to the United States of America and its people, and that his energy and usefulness and skill and honor were exerted at home and abroad for their benefit.”

Several thousand visited his tomb at Old Swedes Church that weekend, newspapers reported.

Bayard’s life was heralded throughout Delaware, nationally and in the United Kingdom.

“This state has lost its foremost citizen and the world a great citizen,” wrote the Dover Delawarean.

“No man in the United States,” The Richmond Times opined, “was more universally respected than Thomas Francis Bayard of Delaware. He was an American nobleman who thought more of country and principle than of political preferment.”

While the 6-foot-1 Bayard was certainly a towering figure from a prominent political family, he actually had a rather complicated relationship with history.

He was among five Bayards to serve in the United States Senate, along with grandfather James A. Bayard Sr. (1804-1813); uncle Richard Bayard (1836-1839/1841-1845); father James A. Bayard Jr. (1951-1864/1867-1869); and son Thomas F. Bayard Jr. (1922-1929).

His great-grandfather Richard Bassett, who was James A. Bayard Sr.’s father-in-law, also represented Delaware in the first U.S. Senate from 1789-1793 and was among the signers of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. He was later governor of Delaware.

The Bayards descended from Stuyvesant Peter, the Dutchman who had been 17th-century general director of the colony of New Netherland, which covered what is now much of the Mid-Atlantic coast into southern New England, including Delaware. His wife was Judith Bayard.

“It’s a proud family history,” said Richard Bayard, who was the third member of his family to serve as Delaware Democratic Party chairman. His father, Alexis I. du Pont “Lex” Bayard, was Delaware’s lieutenant governor from 1949-53 but lost a 1952 U.S. Senate race to incumbent John J. Williams.

U.S. senators were chosen by state legislatures until the Constitution was amended in 1913, giving that duty to voters. Thomas F. Bayard Sr. had been selected by the General Assembly in 1869 to succeed his retiring father, who had returned to the Senate following the death of his successor George Riddle two years prior.

The Democrats were often in the minority when Bayard was in office. But Bayard, a conservative, had already made headlines that followed him throughout his political career.

At the outset of the Civil War, slavery was legal in Delaware, though less than two percent of the population was comprised of slaves, mostly in Sussex County.

Like his father, Bayard had spoken out against war and felt southern states should be allowed to secede if they so desire. Some took exception with his opposition to President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to forcefully fight southern secession, giving the impression Bayard was pro-Confederate, though Bayard did not believe Delaware should join the rebellion.

At a June 1861 “peace meeting” in Dover, Bayard was reported to have calmed an angry crowd and perhaps prevented Delaware from actually joining its southern neighbors, newspapers reported. But Bayard had been part of an independent volunteer militia group and was arrested and briefly imprisoned for refusing to surrender his firearms when the Union army began to form regiments.

Even after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1862 and went into effect Jan. 1, 1863, freeing slaves in Confederate states who escaped to Union-held areas, the Delaware General Assembly stubbornly refused to eradicate slavery in the state. It remained legal until the 13th Amendment officially eliminated slavery at the end of 1865.

After joining the Senate in 1869, Bayard opposed many of the Republican-led Reconstruction efforts resulting in the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments – all initially rejected by Delaware – and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 aimed at voting rights and other forms of equality for oppressed Blacks and former slaves.

Viewing Bayard’s civil rights record through a 20th-century lens, “Our country was fortunate he didn’t make it to the Oval [Office],” News Journal columnist Bill Frank wrote in 1986, when Biden and then-Gov. Pete du Pont were gearing up for 1988 shots at their parties’ presidential nominations.

He did come close.

Bayard was popular in the south for his post-war support and had backers in the North because of his conservative economic record, mainly backing the gold standard to support the monetary system.

Bayard placed a distant fifth at the 1876 Democratic convention, when New York Gov. Samuel J. Tilden was a landslide winner as the nominee. Tilden lost a disputed election to Rutherford B. Hayes, who lost the popular vote by about 250,000 votes but edged Tilden 185-184 in the Electoral tally. A 15-member Electoral Commission, of which Bayard was a member, comprised of congressmen, senators and Supreme Court justices ultimately decided the outcome after voter fraud was discovered in several southern states.

Bayard, by then chairman of the Senate finance and judiciary committees, finished second to Civil War hero Winfield Scott Hancock at the 1880 Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati after first-ballot competition had him just 17½ votes behind. He was then was runner-up to New York Gov. Cleveland in 1884 in Chicago.

Georgetown’s Tansill wrote, citing articles from New York newspapers, that “Bayard’s Dover speech still stalked him on the floor of the convention” in Chicago. There was fear Republicans would use it against him, even while many Democrats expressed their unsurpassed regard for Bayard and faith in his ability to serve as chief executive.

“It would be suicidal to nominate him,” one Congressman said.

In between those two conventions, Bayard was briefly next in line to be president.

At the time, if there was no vice president, the line of succession called for the president pro tempore of the Senate to assume the presidency should it become vacant. Bayard had briefly held that role in 1881 following President James Garfield’s assassination and Vice President Chester Arthur becoming president in September.

According to a 1965 Delaware Today article, Arthur called for a special session of Congress, which wasn’t slated to convene until December, just so there was a designated successor. Though Arthur was a Republican, the Senate was initially in Democratic control. It narrowly elected Bayard as president pro tempore on Oct. 10.

But late-arriving senators from western states gave majority rule back to Republicans. Bayard stepped aside, clearing the way three days later for Republican Illinois Sen. David Davis, who was born in Cecil County, Maryland, to be elected to the post.

After winning the 1884 general election over Maine Republican James Baine, Cleveland selected Bayard as his secretary of state, ending his 16 years in the Senate. Vice President Thomas Hendricks died, however, more than eight months after assuming the office in the fall of 1885.

Once again, Bayard became next in line.

After the Garfield/Arthur situation in 1881, some in Congress felt the Presidential Succession Act should be amended, believing it made more sense to have Cabinet members be appointed instead of elected. The changes were passed by the House and Senate and signed into law Jan. 19, 1986, by Cleveland.

That made his secretary of state, Bayard, as he was for those few days as Senate president pro tempore in 1881, the potential successor should Cleveland die in office. After the secretary of state, the secretaries of treasury and war and then the attorney general were next in line.

More changes were made in the 1940s, when the Speaker of the House was made first in line of succession, and in the 1960s, when an amendment was passed to replace the vice president should that office become suddenly unoccupied.

During his time in government, Bayard continued to operate a law office at Ninth and Market streets in Wilmington

Bayard lived in a mansion that was called Delamore Place located on high ground on the city’s west side at 302 South Clayton Street, near its intersection with Maple Street. It afforded sweeping views of downtown Wilmington and the Delaware River.

Cleveland had visited Bayard at his home on several occasions. Bayard Middle School, bearing the family name, sits there now.

A couple miles away, a statue of Bayard rises along Kentmere Parkway across from the Delaware Art Museum. It was erected in 1907, not just to honor Bayard’s political career but his role in creating the Wilmington park system.

Its plaque includes a quote from Cleveland.

“Bayard is the purest and most patriotic man I know,” it reads.